Pentecostal churches are some of the fastest-growing in the world.[1] A 700% increase over the last thirty years has led Pentecostals to become a quarter of the world’s Christian population. With an estimated 500 million adherents worldwide, converted in the course of one century, Pentecostalism has become one of Christianity’s major branches.[2]Pentecostalism has undoubtedly changed the face of global Christianity and this is apparent in the Australian context. The Pentecostal movement in Australia has grown to over a quarter of a million adherents during the course of the century.[3]

However, recent studies show that the religiousness of Australia is changing fast. The rapid rise in population, cultural diversity and urbanisation is bringing with it changing trends in spirituality. Australia has become more secularised and data from the 2016 Australian census showed that between 2016 and 2011 there was a 9% fall in ‘Census Christians’. This can be evidenced in greater measure within the inner city suburbs of Australia. For example, in the inner city suburb of Waterloo, 42% of Australian census respondents identified themselves as having ‘No Religion’. This is almost double the rate in Australia (29%) and the state of New South Wales (25%).

This rise of ‘No Religion’ census respondents in inner city suburbs forces one to ask, are Pentecostal churches implementing effective outreach strategies capable of reaching the growing ‘No Religion’ population? The data appears to show otherwise. How should churches respond? Ignore the data or use it? Could the data be used to help missional churches strategically respond? To find out, this research paper asks ‘How can demographic data inform the development of missional outreach strategies to the community living in Waterloo, Sydney?’.

To help answer this, first, a literature review is carried out examining the development of Pentecostal missional outreach strategies, the role of demography and the religiousness and spirituality of Australians. Second, the suburb of Waterloo, Sydney, is used as a demographic case study and ‘No Religion’ census respondents are descriptively analysed and compared to the wider suburb population. The two groups are analysed and compared across six demographic variables (Sex, Age in Ten Year Groups, Ancestry, Country of Birth of Person, Social Marital Status and Year of Arrival in Australia), grouped into four demographic measures (Gender, Age, Ethnicity and Marital Status). Third, results are summarised and visualised using charts and graphs. Fourth, demographic findings are discussed through statistical commentary. Fifth, missional implications are explored and concluding thoughts are offered.

Literature Review

The Development of Pentecostal Missional Outreach Strategies

Pentecostal churches are intrinsically missiological[4] and they have developed a “potpourri of outreach practices” to help complete that task.[5] Popular pastoral guide books suggest that movie nights and music concerts, small groups and mass gatherings, community meals and church banquets, euphoric youth nights and multisensory Sunday services are strategies that work.[6] How does a church leader chose the right program and what informs the reasons for his choice?[7] From the author’s experience, that originated out of a decade of planting Pentecostal churches in the UK, and the associated literature, it appears that outreach strategies are often informed by five principal things. First, what is ‘in trend’ or popular at the time among other churches. This is a form of ‘copycat innovation’ commonly found in the marketing sector.[8]Dempster et al. suggest that Pentecostal churches are “inclusive, drawing on ideas, models and strategies from everyone else”.[9] Second, traditional practices or a ‘do what we have always done approach’.[10] Burgunder et al. observe that Pentecostalism throughout its history has tended to become ‘overprotective’ with ideas (where successful ideas are repeated, in turn becoming a tradition and eventually becoming ecclesiological law).[11] Bandy suggests that churches have a tendency to “repeat programs…and fail to terminate ineffective tactics, under an assumption that the community around them has not changed”.[12] Third, the inspiration of individuals. Anderson notes that the growth of Pentecostalism “would not have taken place without the vast number of ordinary and virtually unknown religious entrepreneurs”[13] who have “planned and coordinated sophisticated programs of world outreach”.[14] Individuals whom Chai labels the “multitudes of nameless Christians responsible for the grassroots expansion of the movement”.[15] Fourth, the attractional event-based method that bids anyone to attend and weighs the success on “how many came”.[16] Fifth, community demographic assumptions that are built upon a general understanding of what the local area is like.[17] These five main components that inform Pentecostal church outreach strategies appear to rely upon trend, tradition, inspiration, attraction or assumption.

Although these approaches have informed missional outreach strategies that have led to Pentecostalism being at “the forefront of the expansion of Christianity in the twentieth century”,[18] Cartledge suggests that they are traditional methods that could be enhanced by the inclusion of “methods of social science”.[19] Van der Ven agrees, suggesting that Pentecostal churches should “expand the traditional range of missional instruments, consisting of literary-historical and systematic methods and techniques, in the direction of an empirical methodology”.[20] Despite these assertions, traditionally there appears to have been resistance to this view. As Cerillo observes, “there still remains in the movement a quiet suspicion of too much strategic planning”.[21]

Pentecostal churches appear to prefer less scientific approaches to the development of missional outreach strategies. For example, Hodges suggests that Pentecostal churches rely on the “Holy Spirit…as chief strategist of church evangelism and mission”.[22] Human organisation is justifiable, but only as it reflects divine direction. Chai concurs adding that “Pentecostals place emphasis on being ‘sent by the Spirit’ and depend more on what is described as the Spirit’s leading than on formal strategies”.[23] Anderson adds that amongst Pentecostal churches this ‘freedom in the Spirit’ requires a ‘flexible’ approach to missional outreach strategies,[24] where the church is adaptable enough to respond to those who are “ripe for the harvest”.[25] This approach has been described as ‘creative chaos’ and more reactive than active.[26]Nevertheless, it has been immensely successful and given rise to a movement that has changed the face of global Christianity. However, Cartledge observes that this emphasis on ‘flexibility’ within Pentecostalism, seeks to avoid the “methodological atheism”[27] that empirical data brings, and instead, searches for “spontaneous obedience to the ‘surprise of the Holy Spirit’ without need for calculated strategy”.[28]

Among Pentecostal churches there appears to be a greater emphasis on ‘spirit-led’ not ‘data-driven’ approaches to the development of missional outreach strategies and there are several reasons for this. Saayman suggests that this paradigm arose early in the movements formation and has its roots in the pragmatic and less reflective way Pentecostalism developed. He says that “the Pentecostal movement…was not the result of a clearly thought out theological decision…so methods were formed in the crucible of layman missionary praxis”.[29] This approach, where ‘theology was done on the move’ led to Pentecostal ministry leaders becoming “doers rather than reflective thinkers”.[30] As a result, lay ministers who had been given very little systematic training,[31] ‘flowed with the spirit’ and all other methods were met with suspicion. Cartledge observes that “the idea that theology could have a relationship with the social sciences has had a mixed reception, partly due to the naturalistic reductionism associated with it”.[32] Van der Ven agrees, suggesting that “the idea of empirical theology was a cause for both excitement and caution”.[33]

Nevertheless, Cartledge suggests that “for missiology, with its orientation of engagement with real people in real social contexts, the need to use empirical approaches is fundamental to the discipline”.[34] This notion that data could be used to examine ‘people in social contexts’ was also embraced by Bergunder et al. who recommended that more research should be carried out to help understand the “interplay between Pentecostal practice and local context”.[35] This is where demography becomes useful and its definition and role will now be explored.

The Role of Demography

Demography has been defined as the quantitative study of human ‘characteristics’ within a population[36] (including characteristics such as size, distribution, socioeconomic determinants and variables like age, sex and marital status)[37]and it is suggested to have a variety of uses.[38] For example, demographic data can help describe community characteristics within a population. Several demographic variables such as age, sex, and marital status can be cross-tabulated and findings can help build a community social profile (or demographic picture).[39] Once statistical data has been collected and a demographic picture has been built up, findings can then be used to inform a variety of marketing, governmental, social scientific and religious strategies.[40]

The use of demography within religion is also observed by Dillon who suggests that “demography and religion have a fruitful past and a promising future”.[41] Ma et al. agree, noting that demographic data is regularly used by churches and has a vital role to play within them.[42] For example, the literature suggests that demographic data is commonly used in the “developmental phase of pioneer church planting” to direct targeted missional outreach strategies within specified localities.[43] McClung suggests that “churches, after learning about their city’s diverse economic and social demographics, have the means to be flexible and focused in how they do mission”.[44] Similarly, demography is fundamental to the Homogeneous Unit Principle (HUP) that views positively the rationale for starting churches that are made up of people who are demographically alike (a practice that appears to be contested).[45] Likewise, demography is central to the study of religiousness and spirituality. McAleese et al. used demographic data from the 2016 National Church Life Survey and the 2016 National Census of Population and Housing to explore “some of the changing demographics of Australia and its churches”.[46] Demographic variables such as age, education, employment status, country of birth and marital status were used to help paint a picture of the communities surrounding churches (a demographic profile). The information was then offered to churches to help them develop and structure missional outreach strategies. Pepper et al. also produced demographic data that could be used by churches to help design mission strategies. Their 2018 Australian Community Survey assessed current attitudes toward religion, evaluated people’s level of contact with churches and highlighted factors that influence an openness to accepting an invitation to attend church.[47] This usefulness of demographic data in the study if religion is also observed by Dillon who asserts that, although “the sociology of religion may not overlap with demography in many people’s minds…a demographer’s concepts and methods…can help shape the religious landscape”.[48]

Dillon’s comments suggest that demography can be of great value to Pentecostal church leaders and literature reveals five ways in which demographic data can inform and enhance missional outreach strategies. First, it can help specify the community characteristics surrounding the church (within any radius). As Bandy puts it, “demographic research provides a way to see more clearly the current and future realities of the people who live within your church’s reach”.[49] Second, it can help highlight populations of people that share similar religious profiles. Findings can then help “indicate any unreached people group that needs the gospel”.[50] Ott adds that any highlighted population may then become a selected ‘focus people’ chosen for strategic missional outreach.[51] He also adds that there appears to be a theological and missiological argument for this prioritised approach.[52] Third, it can show population attitudes toward religion (like aspects that attract to or repel from Christian faith) and responses to specific missional strategies (like the openness to accepting an invitation to a church by a close family or friend).[53] The findings can then “predict a person’s future behaviour and…can be used as a way to segment a market”.[54] Programs can then be developed to help meet the needs of the individual demographic populations.[55] Fourth, it may help to innovate and inform targeted missional outreach strategies to specific populations or enhance existing ones. Bandy asserts that “Christian leaders can design mission” and the reason one tactic is chosen over another can be rooted “not in individual intuition but objective research”.[56] This does not necessarily mean that “intuition or being ‘spirit led’ is unimportant… even when all the data has been collected…the human factor and the Spirit factor are still there”.[57] Nevertheless, Howard suggests that “grounding discernment in data” can help church leaders create “effective missional strategies” relevant to a churches context.[58]This strategic use is based on the idea that people with unique characteristics have different needs and aspirations. Also, Bandy adds that this strategic approach has the added benefit of helping church leaders to “perfect ongoing programs and terminate ineffective ones”.[59] Fifth, it may help to avoid a mismatch between church and community context and ensures that outreach strategies meet the needs of the localised community.[60]

However, despite the suggestions that demographic data is helpful, there appear to be some limitations to its use. Hodges suggests that data-driven missional approaches primarily lead to numerical growth, and this does not provide the guarantee that a person will embrace Christian belief or genuine conversion. He further emphasises that there is a need to focus entirely on ‘conversion strategies’ (not growth strategies) and asserts that the measure of “success in promoting the Kingdom of God must be measured by the number of people it can bring into a vital relationship with Christ”.[61]Conversely, Dempster disagrees and suggests that the ‘ethos of growth’ that motivates Pentecostal churches is of significant benefit to Christianity at large. He states that “in a time of defeatism, stagnation, and retreat in many churches, a growth climate may prove to be one of the great bequests of Pentecostalism”.[62] Therefore, these arguments appear to suggest that, although the use of demographic data cannot lead to Christian conversion, its suggested ability to fuel growth is of great value to Pentecostal church leaders. This paper seeks to understand the value of demographic data within the Australian community and the spirituality of this context will now be explored.

The Religiousness and Spirituality of Australians

Pepper et al.’s comparison between the 2016 Australian population census and the 2016 National Church Life Survey showed that there have been several observable religious changes in Australian communities.[63] Their findings suggest that Australia has become more secularised and the population census shows that “those who indicated Christianity as their religion…has fallen”.[64] Between 2016 and 2011 there was a decrease of nine hundred and fifty thousand ‘Census Christians’. This is equivalent to a 9% fall in five years (between 2016 and 2011). Pepper et al. suggest that this decline is largely due to Australian secularisation and the large number of ‘No Religion’ census respondents. Also, the same report noted an increasing demographic mismatch between local congregations and the wider Australian population. Indicators from seven Christian denominations (Anglican, Baptist, Catholic, Lutheran, Pentecostal, Uniting and ‘Other Protestant’) showed that church attenders, compared to the broader Australian population, are more likely to be: older, female, university educated, born in a non-English speaking country, married or widowed and unemployed (with the latter two variables likely linked to the aging profile of church attenders).[65]

Similarly, Powell et al.’s 2018 sample survey of 1200 Australians aged 18+ outlined additional changes to Australia’s religious climate, namely the rise of ‘no religion’ populations.[66] Their cluster analysis that grouped Australia’s survey respondents into four types (practising religious and spiritual, non-practising religious and spiritual, spiritual but not religious and neither religious nor spiritual) found that a dominant number of census respondents (35%) could be categorised as ‘neither religious nor spiritual’.[67] A large majority of that ‘neither religious nor spiritual’ population (70%) did not identify with a religion at all. They were either atheist or agnostic, did not attend church and accepted that miraculous experiences did not occur.[68] Bouma also observed this rising trend of ‘no religion’ survey respondents, stating that “recent demographic developments…reveal a new religious context in Australia with the growth of a major No Religion sector”.[69] This population was further studied by Mason et al. and their findings showed that the Australian ‘No Religion’ population largely consisted of two views: those who are irreligious (where religion is meaningless) and those who are actively anti-religious.[70] However, they also found that “if they are under 30 years old, many have a ‘whatever’ attitude toward religion” and this results, not from indifference or ignorance, but the century relative ‘sea of superdiversity’ in current Australia.[71]

It is clear then, that largely because of superdiversity, the ‘No Religion’ population in Australia is growing and the trend appears to be continuing. For example, the 2016 Australian Census showed that respondents declaring they had ‘No Religion’ had increased by 7.3% since 2011. This is the largest census rise since 1911.[72] In the space of five years, the ‘No Religion’ census respondents had moved from the second most common population to the first. Nationwide ‘No Religion’ census respondents are now the largest religious population in Australia (listed under the ‘Religious Affiliation’ category).

This rising ‘No Religion’ trend appears to pose a challenge to Pentecostal churches. For example, it seems to suggest that mission-oriented churches do not have effective outreach strategies capable of reaching the growing ‘No Religion’ population (otherwise the population would not be growing). How should churches respond to this? Disregard the data or draw from it? If Pentecostal churches were to draw for the data and attempt to ‘reach the unreached’, who are they reaching, what characteristics make up the ‘No Religion’ census respondents and which missional strategies could be used to engage with them? Furthermore, could demographic information help missional churches strategically respond? To find out, this research project investigates whether demographic data can help inform the development of missional outreach strategies and uses the community living in Waterloo as a case study. The history of this area and the reason for the site selection will be explored in the next section.

Waterloo Case Study

A Brief History

The inner city suburb of Waterloo, which is located three kilometres south of Sydney’s central business district, has had a changing historic, demographic and religious history. Historically, the suburb was established in 1815 and has been described as an “old industrial and residential area” that is currently going through gentrification.[73] It was characterised by manufacturing in the nineteenth century, public housing in the twentieth and now is suggested to be going through developmental urbanisation. This changing history has several developments. The Pre-European area of Waterloo was a natural landscape covered in wetlands. During the Post-European 1800s, local investors began searching for industrial power sources to fuel their mills and eventually the wet landscape, and the consequent steam power produced from it, led Waterloo to become an industrial hub. Over time, grains mills gave way to large-scale industrial factories. Frith notes that “by 1943, the area boasted 550 factories, and was the largest industrial municipality in Australia”.[74] However, overtime heavy industry gave way to ‘urbanisation’ and the present-day public housing, apartment blocks and contemporary cafes appear to be evidence of that. Demographically, the settlement of Irish, Maltese, Lebanese and Greek occupants led Waterloo to be marked as ‘multicultural’. The continuous presence of Chinese occupants since 1870s also began to define the region.[75] Although the number of Chinese occupants has fluctuated considerably, “during the 1880s and early 1900s the suburb accommodated the highest concentration of Chinese people in Sydney”.[76] O’Reilly notes that “by 1971, nearly 40% of the inhabitants of Waterloo were immigrants” and, as Australian Born Chinese (ABC) children were born, the suburb became known for its diversity. This diversity still exists today and currently, Waterloo is occupied primarily by a mix of Australian, Chinese and English occupants. Also, Waterloo’s changing religious history has been documented and the religious practices common in Waterloo appear to reflect its multicultural heritage. O’Reilly notes that “the early Irish presence saw the establishment of Mt Carmel Catholic Church, which later provided the place of worship and spiritual guidance for the increasing Maltese and Lebanese communities”.[77] Australia’s first Maronite and Melkite churches were founded in Waterloo, reflecting the high level of Lebanese and Greek immigration to the area. Furthermore, Rogowsky notes that due to the common Asian practise of weaving different beliefs together, Chinese occupants began practising an amalgamated version of both Christian and Eastern beliefs.[78] Karskens suggests that the close proximity of the Yiu Ming Daoist Temple (in Alexandria) to the Soo Hoo Ten Church of England (in Waterloo) points to the suburbs syncretistic past. It is evident then, that Waterloo has had a changing historic, demographic and religious history and contemporary changes can still be observed. The current changes (that centre around religious affiliation) are one of the reasons why Waterloo was chosen as a case study and this will explored in more detail in the next section.

Site Selection

The suburb of Waterloo has been chosen for this research project for two main reasons. First, it is an extreme case study that helps illustrate the previously mentioned rise of ‘No Religion’ census respondents in Australia. For example, in the inner city suburb of Waterloo, 42% of census respondents identified themselves as ‘No Religion’ (this being the most common response in the ‘religious affiliation’ category). This is almost double the rate in Australia (29%) and the state of New South Wales (25%). In short, Waterloo is an important area because it is an inner city suburb in the biggest City of Australia and has the highest concentration of ‘No Religion’ census respondents in the country. Second, the urbanised suburb of Waterloo appears to be directly relevant to the Pentecostal ‘urban heritage’ inherited from the cosmopolitan Los Angeles of 1906”.[79] Research into religion in the city is particularly important for a number of reasons. If the Pentecostal movement “begun in a city and continues to be at home in urban areas”[80] and if Pentecostal churches “find their strength in the city”,[81] then the dominance of the ‘No Religion’ census respondents in inner city Waterloo appears to be an observation that justifies further examination. Research is needed to help understand the ‘No Religion’ census respondents in Waterloo so that the information gathered can be used to help inform relevant and suitable missional outreach strategies. The information and data needed will be gathered using suitable methods and these will be outlined in the next section.

Methodology

Research Method

To find out whether demographic data can inform the development of missional outreach strategies to the community living in Waterloo, this project followed a quantitative research method. Quantitative research is an empirical investigation that seeks to explain phenomena according to numerical data.[82] Since the research project centres around the usefulness of data, this approach appears to be the most suitable method for answering the research question. Quantitative research is often the preferred method for demographers carrying out population studies, and therefore, appears to be an appropriate approach to the study of the ‘No Religion’ population in Waterloo. Quantitative methods offer high levels of reliability, validity and objectivity. The measurable nature of quantitative data means that interpretations and findings are based on measured quantities rather than impressions.[83] One disadvantage of using quantitative data is that it cannot always be used to explain social phenomena – often it can explain what is happening, but not always why.

Data

External secondary data was collected from the 2016 Australian Census of Population and Housing. Demographic data was gathered using TableBuilder Basic, which is the Australian Bureau of Statistics online tool for creating cross-tabulated tables from Census data. Using census data was useful as it gave an opportunity for a comparison between the entire population of Waterloo and ‘No Religion’ census respondents within the community. Also, the 2016 Australian Census offers comprehensive data that is objective, valid and reliable. It is commonly used by demographers and social scientist and independently reviewed by a panel of international statisticians and academics.

Sample

Two data samples were collected from the 2016 Australian Census of Population and Housing and these were: 1) the entire population of Waterloo and 2) ‘No Religion’ census respondents living in the suburb. The entire population of the suburb of Waterloo was found to be 14,621 and of these 6076 were ‘No Religion’ census respondents (42%).

Measures

Frequency counts were retrieved and percentages were calculated for thirteen demographic variables and these were: Sex, Age in Ten Year Groups, Ancestry, Country of Birth of Father, Country of Birth of Mother, Country of Birth of Person, Year of Arrival in Australia, Australian Citizenship, Indigenous Status, Registered Marital Status, Social Marital Status, Number of Children Ever Born and Total Personal Weekly Income. Preliminary analysis was conducted and demographic variables were grouped into four demographic measures and these were: Gender, Age, Ethnicity and Marital Status. Of the thirteen demographic variables, six appeared to be more relevant to this research project. Therefore, Sex, Age in Ten Year Groups, Ancestry, Country of Birth of Person, Social Marital Status and Year of Arrival in Australia were selected for further analysis.

Analysis

The collected demography was analysed using descriptive statistical analysis.[84] This appears to be a standard method for the analysis of demography and is appropriate for this research project as it provides valuable information about the characteristics of a particular population (however this also means it is not generalisable).[85] Descriptive research seeks to summarise data and is often used to provide: a) first estimates, summaries and visualisations (arranged in tables, charts and graphs), b) frequencies and measures of central tendency, c) an indication of data patterns and d) a comparison between populations.[86] To carry out statistical analysis, demographic variables were summarised and described in frequencies (in percentages) and measures of central tendency (mean, median and mode). Also, to further analyse the data comparison was made between ‘No Religion’ census respondents and the entire population of the suburb of Waterloo. To help summarise the data, results were visualised using bar charts and line graphs and these are presented in the next section.

Case Study Results

Gender

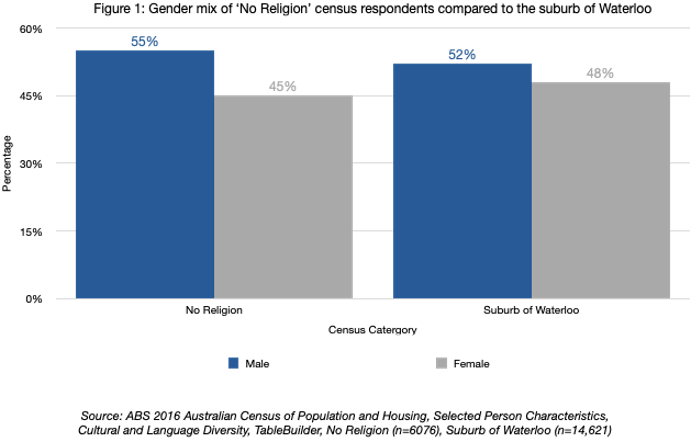

Figure 1 shows the gender mix of ‘No Religion’ census respondents compared to the suburb of Waterloo. Results show that ‘No Religion’ census respondents were more male (55%) than female (45%). Similarly, the suburb of Waterloo was more male (52%) than female (48%). In comparison, ‘No Religion’ census respondents are marginally more male and less female than the suburb of Waterloo.

Age

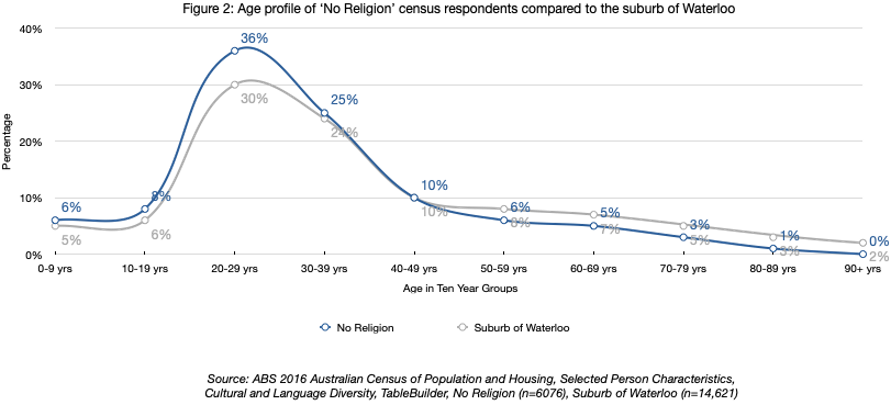

The 20-29 years age category had the highest percentage of ‘No Religion’ census respondents (36%), as shown in Figure 2 below. People aged 20-39 years made up 61% of ‘No Religion’ census respondents. This is younger than the average age of ‘No Religion’ census respondents (44 years) and the suburb of Waterloo (48 years).

Ethnicity

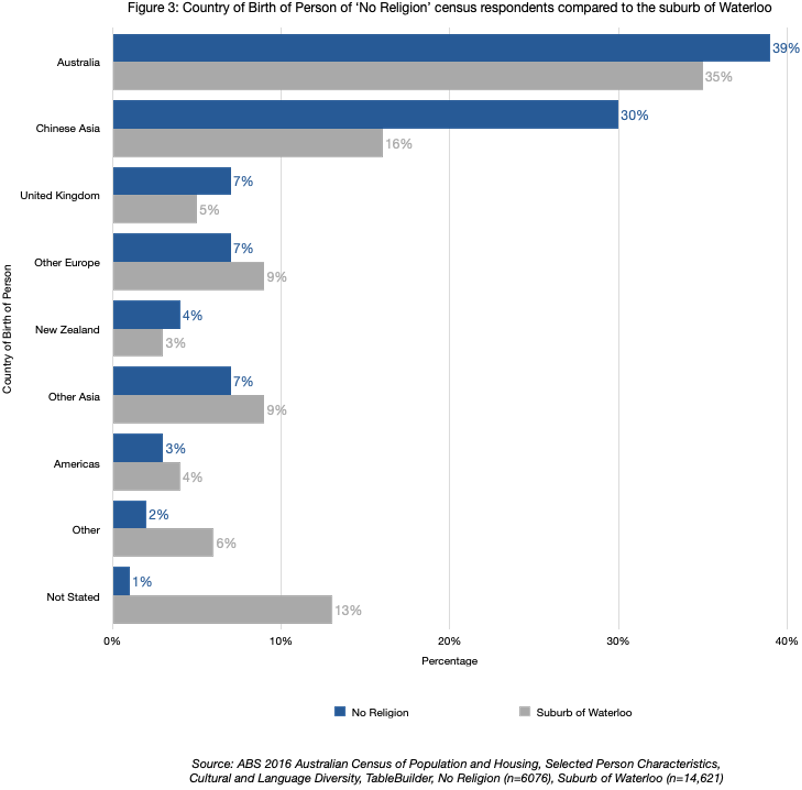

Figure 3 shows that 39% of ‘No Religion’ census respondents were born in Australia compared to 35% in the suburb of Waterloo. The second most common country of birth of ‘No Religion’ census respondents was Chinese Asia (30%). In the suburb of Waterloo, only 16% were born in Chinese Asia. There are twice as many Chinese Asian born ‘No Religion’ census respondents (30%) than the suburb of Waterloo (16%).

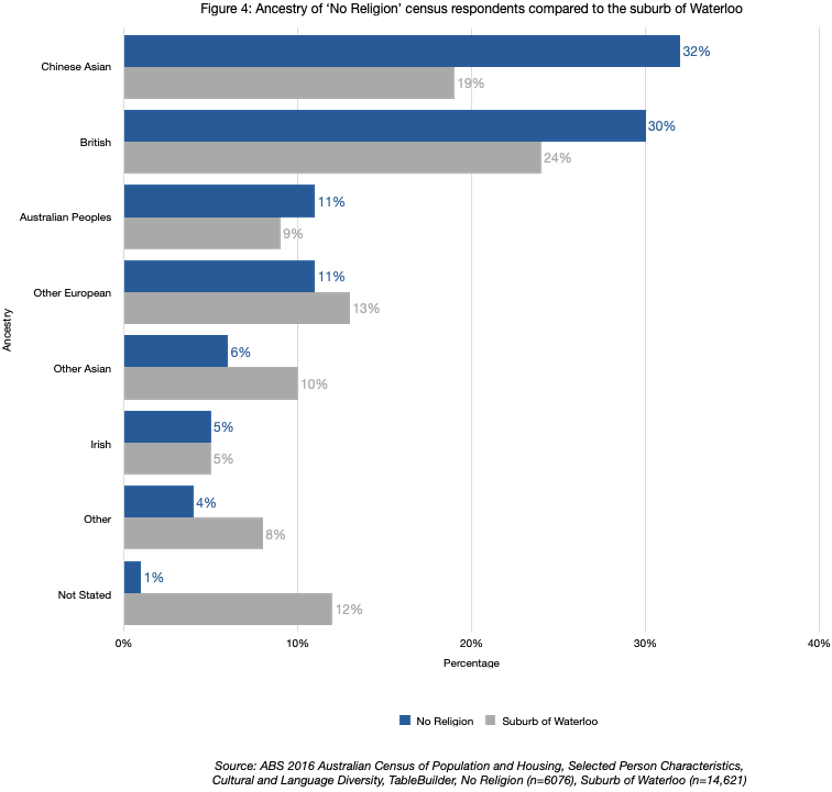

32% of ‘No Religion’ census respondents were of Chinese ancestry compared to 19% in the suburb of Waterloo, as seen in Figure 4 below. The second most common ancestry of ‘No Religion’ census respondents was British (30%) compared to 24% in the suburb of Waterloo. The suburb of Waterloo had more British ancestry (24%) than Chinese (19%). ‘No Religion’ census respondents had more Chinese (32%) than British ancestry (30%).

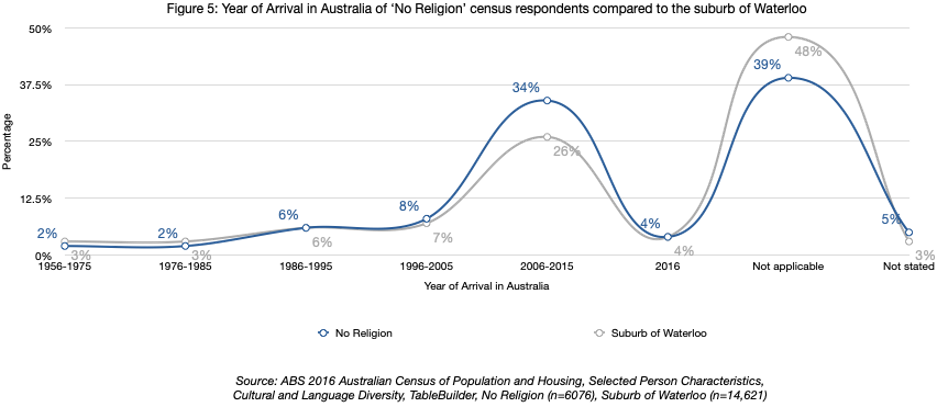

Figure 5 shows the year of arrival in Australia. 39% of ‘No Religion’ census respondents were born in Australia compared to 48% in the suburb of Waterloo. In the suburb of Waterloo, more people were born in Australia compared to ‘No Religion’ census respondents. 34% of ‘No Religion’ census respondents arrived in Australia between 2006-2015 compared to 26% in the suburb of Waterloo. In the suburb of Waterloo, fewer people arrived in Australia between 2006-2015 compared to ‘No Religion’ census respondents. The median year of arrival to Australia was 1996. The majority of ‘No Religion’ census respondents arrived after that date or were born in Australia.

Marital Status

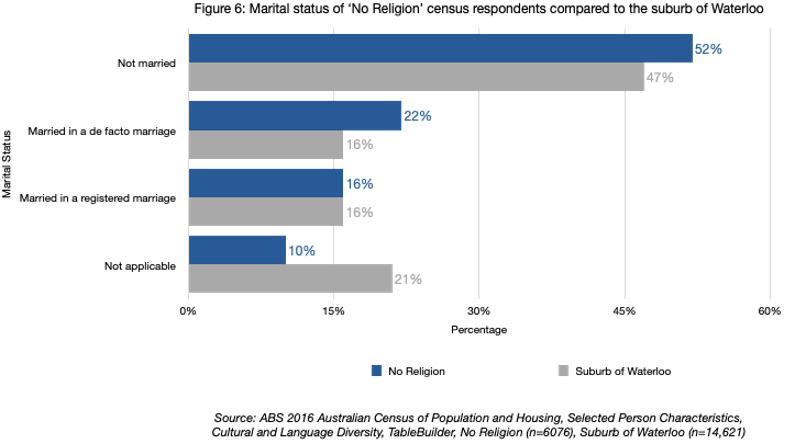

52% of ‘No Religion’ census respondents were not married compared to 47% in the suburb of Waterloo. 22% of ‘No Religion’ census respondents were in a de facto marriage compared to 16% in the suburb of Waterloo. 16% of ‘No Religion’ census respondents were in a registered marriage and this was the same in the suburb of Waterloo (16%). The majority of ‘No Religion’ census respondents were either not married (52%) or in a de facto marriage (22%) and this reflects the pattern in the suburb for Waterloo.

Findings and Discussion

This research project investigated whether demographic data could help inform the development of missional outreach strategies to the community living in Waterloo. To do this, ‘No Religion’ census respondents were selected as a ‘focus group’ and descriptive statistical analysis was used to help outline the demographic profile of this population sample. Results showed that the largest percentage of ‘No Religion’ census respondents had four key features, they were: male, aged 20-29 years, Chinese Asian either born in Australia (Australian Born Chinese) or arriving between 2006-2015 and unmarried. This section offers a statistical commentary on the results and looks at the possible reasons for them.

Gender Mix

‘No Religion’ census respondents were more male than female. Also, when compared to the entire population of Waterloo, ‘No Religion’ census respondents were more male and less female than the suburb. Interestingly, these results differ when compared to the entire population of Australia, where nationwide women marginally outnumber men. However, Opeskin et al. note that inner city Sydney is one of only two areas that have more males than females and suggests that “this pattern may be linked to the location of Sydney to these areas, and the resultant high proportions of young working-age males”.[87] The high number of male ‘No Religion’ census respondents was not surprising.[88]Studies show that men are less represented in religion. Australian research investigating gender distribution and church attendance points to a “skew towards females”.[89] McAleese et al. observe that across seven Christian denominational groups 60% of church attenders are female and 40% male. The results for No Religion’ census respondents support those findings.

Age Distribution

The largest percentage of ‘No Religion’ census respondents were aged between 20-29 years and were younger than the median age of Waterloo. This reflects the age distribution pattern in Sydney and inner city areas. Opeskin et al. note that “Sydney’s population has a higher percentage of its total in the 20-44 years age range”[90] and find that “for the 20-24 year age group, it is the inner city areas of Sydney that have the highest percentages”.[91] This is likely due to young workers seeking opportunities to be within walking distance to work, cafes, bars and other entertainment precincts.[92]Also, this age distribution pattern appears to reflect Sydney’s mobility. In particular the “net gains of young adults due to internal and international migration and net losses of both children and middle-aged and older adults due to internal migration”.[93] Bernard agrees, suggesting that “migration is an age-selective process, young adults being the most mobile group”.[94]

Ethnicity

Chinese Asians, who were either born in Australia or arrived between 2006-2015, were the largest percentage of ‘No Religion’ census respondents. Tao et al. found similar findings and observed that “empirical information derived from the census, shows a high level of secularity among the Chinese community in Australia” [95] (although it is still possible for them to believe in certain spiritual concepts such as karma or reincarnation).[96] These results are likely linked to Waterloo’s historical diversity resulting from high levels of international migration, its industrial past leading to modernisation and the secularising effect that this has.[97] As mentioned in the literature review, in the 1900s Waterloo accommodated the highest concentration of Chinese people in Sydney and in the 1970s many Australian Born Chinese (ABC) children were born in Waterloo. More recently, the Australian Government’s immigration policy changed, from attracting general migrants to focusing on attracting skilled migrants through the formal ‘Migration Program for skilled and family migrants’.[98] As a result, Opeskin et al. note that “in 2009-10 China was the single most important source country for permanent additions to the New South Wales population through international migration”.[99] Their observations may explain the spike in Figure 5 between 2006-2015, which is likely because of the Migration Program for skilled and family migrants.

Marital Status

The majority of ‘No Religion’ census respondents were not married and this reflects the marital pattern throughout the suburb. This may be due to the previously mentioned influx of young adults into the suburb of Waterloo and the social trend of marrying later in life.[100] However, the findings are not surprising, given that, marriage rates in Australia have been decreasing since the 1970s.[101] Kiernan et al. also observe the increase in de facto marriage relationships (including same sex-couples) and links this to the announcement of marriage-equivalent rights, where cohabiting couples are treated in the same way as married couples.[102] The decrease in marriage rates and the rise in de facto marriage also suggests that the demographic mismatch between church and community is widening. This is because, as McAleese et al. observe, there are higher percentages of married Australian church attenders compared to those not married. The demographic results from this research paper appear to reflect their findings and this suggests that more effective missional strategies need to be designed to help churches engage with not married populations. The design of missional strategies such as these will be discussed in the next section.

Missional Implications

The key findings from the demographic data suggest that the highest percentage of ‘No Religion’ census respondents in Waterloo were: male, 20-29 years old, Chinese Asian (either born in Australia or recent arrivals) and unmarried. As such, missional outreach strategies focusing on this population need to be designed with this demographic profile in mind. This paper recommends that missional outreach strategies to the highest percentage of Waterloo ‘No Religion’ census respondents should be designed to effectively engage with:

Men

Missional outreach strategies in the suburb of Waterloo should be designed around effective male engagement if they are to reach the higher number of male ‘No Religion’ census respondents observed in this study. The relationship between gender and religion has been a widely discussed topic and it is commonly understood that there are considerable differences between men and women in their religious behaviour.[103] Saroglou et al. suggest that “generally women are found to be more religious than men (although it is not always the case)”.[104] Several theories have been developed in an attempt to explain this phenomenon, including sociological theories (socialisation, position in society, risk aversion and power control) and psychological gender difference theories (psychological characteristics and personality traits).[105]While there is still no agreement about which factors are most important, it is evident that missional outreach strategies designed to attract more male populations than female will likely take on a different shape. Further research would be needed to investigate which (if any) specific Pentecostal missional outreach strategies to inner city men are effective and why. However, Morley et al.’s pastoral book, written by the National Coalition of Ministry to Men, asserts that male shaped mission strategies must “focus primarily on establishing relationships, not on developing programs”.[106]Rainer’s pastoral book agrees, suggesting that men should be engaged through relationship because they are “more reluctant to go to a church where they know no one”.[107] Pepper et al. appear to support this link between relationship and church attendance. Their study showed that a low percentage (14%) of ‘No Religion’ survey respondents (both male and female) knew ‘close others’ who regularly attend a Christian church. The same ‘No Religion’ population were also least likely to accept an invitation to church (6%).[108] This suggests that there is a link between relationship and church attendance, and therefore, relationally connecting Waterloo’s male ‘No Religion’ population to regular church attenders may be an effective missional outreach strategy. Also, as previous literature suggests, male ‘No Religion’ census respondents are thought to be young male workers, and as such, work-based or industry-related relationship-building methods based around the concept of ‘mateship’ may prove useful.[109]

20-29 year olds

Any missional outreach strategies to ‘No Religion’ census respondents in Waterloo should be primarily designed for the 20-29 year olds. At the time of this paper, 20-29 year olds would have been born between 1991-2000 and are likely to be known as Generation Y and Z. This “mobile and extremely media connected”[110] population are a key demographic group that is often targeted by the marketing sector (often being engaged using generational market segmentation practices). Commonly, the population are defined in terms of multiculturalism, postmodernism, internet evolution and social multi-media communication, where sharing information is power.[111] Powell suggests that 20-29 year olds have active and various leisure patterns and a preference for enjoyment and excitement.[112] Williams et al. observe them to be image-driven, often making personal statements with their image. Schewe also observes a preference for individualised apparel and electronic gadgets.[113] Despite the variety of enlightening descriptions that help outline the sociological dimensions of 20-29 year olds, Smith et al. suggest that the dominate feature of this population is their dependence on multi-platform social media networks.[114] The Pew Research Centre supports this, showing that “of all age groups, 18-29-year-olds drive the most social media consumption (88%)”.[115] This occurs across four main platforms, including YouTube, Facebook, Instagram and Snapchat.[116] Although further research would be needed to investigate the effective use of these platforms to engage inner city 20-29 year olds, there is evidence to suggest that social media may be a key tool in the design of Pentecostal missional outreach strategies to ‘No Religion’ census respondents in Waterloo.[117]Studies into the growth of Pentecostalism support this and show that social media helps ‘move religion’. Social platforms “become intermediaries through which people can experience the divine”.[118] Hackett et al. also suggest that this can result in conversions and reconversions.[119] Nyamnjoh agrees, stating that social media communication tools can be used to “lure others to be born-again”.[120] This approach, therefore, appears to be an effective way to address the worldwide religious decline among this specific age group.[121]

The Chinese Asian Community

The Chinese Asian component of ‘No Religion’ census respondents in Waterloo has been drawn out through this research. Therefore, missional strategies should be designed around the Chinese Asian population in this area with an emphasis on effective and accepted cross-cultural engagement. Although further research would be needed to investigate the particular methods used in inner city Waterloo, Zhang’s study on Chinese conversion to Christianity highlights some helpful approaches.[122] He observes that effective missional outreach strategies to Chinese communities often requires the involvement of already ‘converted’ Chinese Christians and ‘parachurch’ organisations. This helps remove or overcome language ‘barriers’ and any initial cultural distrust.[123] He also observes the need for Mandarin and Cantonese language translation during events or services and noted that this is particularly important for first-generation immigrants. Austin finds that the foreign language component can be used to a churches advantage, as a useful missional outreach tool, especially when taking the form of free English classes for Chinese communities.[124] Zhang advocates social bonding through ‘cell groups’ that target Chinese families in different areas (divided into Chinese language, age, occupational status and gender). Of particular use were ‘pre-evangelism’ strategies, such as welcoming new arrivals (using airport pickup and transport), offering practical help (with routine tasks), the observance of cultural celebrations (such as Chinese New year) and general community engagement strategies. The emphasis on genuine community appears to be the primary mechanism for Chinese Asian community engagement. Cao supports this and suggests that churches can act as ‘surrogate families’ to Chinese immigrants. He suggests that the strength of this familial concept is based upon the idea that Chinese cultural contexts are drawn to the ‘openness’ of Christian groups (where ‘others’ are let into one’s life) and the expression of affection (like that which is observed in ‘the emotional style of the church’).[125] His research suggests that this approach is particularly useful when attempting to engage young Chinese Asian adults and therefore has direct relevance to this research paper.

Unmarried People

Engaging with unmarried people should be the focus of missional outreach to ‘No Religion’ census respondents. Such an approach not only takes into account the large unmarried population in inner city contexts but also the demographic profile of ‘No Religion’ census respondents living within Waterloo. Although further research would be needed to match the unmarried population with their specific relationship status (such as never married, divorced, widowed, single-parent and separated person), Franck asserts that churches should have “a specific, targeted unmarried ministry”.[126] In his pastoral book based upon grounded research, he advocates missional strategies that are designed around six dimensions of unmarried life and these are spiritual, social, mental, physical, relational and emotional. He suggests that share groups, ‘getaways’, seminars and workshops are popular among unmarried populations and can be used to promote Christian spiritual life. Social events that embrace fun, laughter and the experience of new activities or skills can be used to help initiate engagement between ‘the unchurched’ and Christians (a factor necessary for effective mission). Mentally stimulating, creative, educational and career-based classes can help gather unmarried people into Christian communities. Also, physical fitness initiatives (physical), relational activities (relational) and pastoral care (emotional) can be used as outreach mechanisms to help gather unmarried populations into Christian communities. Also, Franck observes that ‘being in family’ is often attractive to unmarried populations and suggests “unmarried populations need community…more than married ones do”. The need for connection and inclusion is best understood in terms of being ‘family-ed’. This can be achieved through a variety of ‘positive belonging experiences’, including social small groups, neutral location age group events and various open discussion forums. Approaches such as these offer “opportunities for a relationship with other unmarried people who have interests and issues similar to theirs”.[127] Furthermore, practically addressing the ‘needs’ of unmarried populations through themed teaching and preaching services focused on relevant topics appears to be an effective strategy. Topics such as premarital and re-marital education, relationships with the opposite sex, career issues, singleness and relationships are suggested by some to be appropriate.[128] However, despite the variety of missional suggestions, further evaluative research would be needed to investigate which (if any) missional outreach strategies are effective in inner city Australian contexts.

Limitations

Although the demographic findings have helped inform mission strategy, there were limitations within this research project. The 2016 Australian Census of Population and Housing data was four years old, and therefore, results and recommendations are appropriate to that year. Also, the generalisability of the results could only be limited to the ‘No Religion’ census respondents in the suburb of Waterloo. Further research would be required to investigate other suburbs or populations. Also, due to the lack of available data, the results were limited to Selected Person Characteristics (or demographic variables) listed on TableBuilder. For example, the education profile of ‘No Religion’ census respondents in the suburb of Waterloo was listed in a different data set/table, making it unavailable for this research. Also, it was beyond the scope of this paper to recommend specific/detailed missional outreach strategies, and therefore, further research is needed to establish which missional outreach strategies (if any) can be implemented to effectively address the four key demographic features of the ‘No Religion’ census respondents in the suburb of Waterloo.

Conclusion

This research paper asked, ‘How can demographic data inform the development of missional outreach strategies to the community living in Waterloo, Sydney?’. To arrive at an answer, this paper reviewed the current literature and explored the development of Pentecostal missional outreach strategies, the role of demography and the religiousness and spirituality of Australians. The suburb of Waterloo, Sydney, was chosen as a case study and an appropriate history of the area was outlined. Next, quantitative descriptive statistical analysis of 2016 Australian demographic census data was used to investigate two populations (or ‘focus groups’), they were the ‘No Religion’ census respondents living in the suburb and the entire population of Waterloo. The two groups were analysed and compared across six demographic variables (Sex, Age in Ten Year Groups, Ancestry, Country of Birth of Person, Social Marital Status and Year of Arrival in Australia), grouped into four demographic measures (Gender, Age, Ethnicity and Marital Status). Visualised results showed that the largest percentage of ‘No Religion’ census respondents had four key features, they were: male, aged 20-29 years, Chinese Asian (either born in Australia or arriving between 2006-2015) and unmarried. The findings were discussed and a statistical commentary outlined the possible reasons for them. The missional implications were then explained and demographic results and findings were used to inform missional outreach strategies to the highest percentage of ‘No Religion’ census respondents living in the suburb of Waterloo. Based upon the four key demographic features, the paper recommended that missional outreach strategies to the highest percentage of ‘No Religion’ census respondents should be designed to effectively engage with: Men, 20-29 year olds, The Chinese Asian Community and Unmarried People.

As such, the paper addressed the research question and showed that demographic data can inform the development of missional outreach strategies. Demographic data was found to have a variety of uses within mission strategy design and these reflected what was outlined in the literature review. As previously mentioned, demographic data helped specify and describe the population characteristics of the suburb of Waterloo and from this, a community demographic profile and picture was built up. This is important because missional outreach requires an understanding of local context. Also, it helped highlight populations of people that shared similar religious profiles and in this case ‘No Religion’ census respondents were found to be the dominant ‘focus group’. Additionally, demographic data provided specific information to help describe the profile of this population so that key features could be drawn out and used to inform mission strategy. Moreover, data helped to recommend missional outreach strategies based upon key demographic features relevant to the context (a form of market segmentation, as previously mentioned). The basis of this idea is that different people with different characteristics have different needs, aspirations and ways of communicating (for example 20-29 year olds were found to be more likely to respond to multi-platform social media campaigns, whereas Chinese Asian communities required linguistic translation). Furthermore, demographic data may be helpful to assess and enhance ‘existing’ missional outreach strategies by providing information about particular populations (although this was untested as it was beyond the scope of this research). Existing strategies could likely be adjusted, adapted, refined or eliminated based upon demographic findings. As previously mentioned, this may prove useful for Pentecostal urban outreach by advocating a more active rather than reactive approach. Finally, the result of using demographic data would likely be, not a mismatch between church and community, but a matched assimilation. As a result, ‘spirit-led’ Pentecostal mission would not be hindered by ‘data-driven’ contextual findings. In fact, this paper argues that it would be enhanced by it. However, it is also apparent that demographic data cannot lead to Christian belief or genuine conversion, nevertheless, demography and religion appear to have a fruitful past and a promising future.

[1] Teresa Chai, “Pentecostalism in Mission and Evangelism Today,” International Review of Mission 107, no. 1 (2018): 129.

[2] Michael Bergunder et al., eds., Studying Global Pentecostalism: Theories and Methods, The anthropology of Christianity 10 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2010), 1-2.

[3] Shane Clifton, Pentecostal Churches in Transition: Analysing the Developing Ecclesiology of the Assemblies of God in Australia (BRILL, 2009), 1.

[4] Andrew Lord, Network Church: A Pentecostal Ecclesiology Shaped by Mission, Global Pentecostal and charismatic studies v. 11 (Leiden ; Boston: Brill, 2012), 3.

[5] L. Grant McClung, “Theology and Strategy of Pentecostal Missions,” International Bulletin of Missionary Research12, no. 1 (2012): 3.

[6] David Stark, Reaching Millennials: Proven Methods for Engaging a Younger Generation (Minneapolis, Minnesota: Bethany House, a division of Baker Publishing Group, 2016).

[7] Grant McClung, Azusa Street & beyond: Missional Commentary on the Global Pentecostal/Charismatic Movement(Gainesville, Fla.: Bridge-Logos, 2012), 208.

[8] Femke van Horen and Rik Pieters, “Consumer Evaluation of Copycat Brands: The Effect of Imitation Type,” International Journal of Research in Marketing 29, no. 3 (September 1, 2012): 246–255.

[9] The Globalization of Pentecostalism: A Religion Made to Travel (Eugene: Wipf & Stock Publishers, 2011), 254.

[10] PhD White Peter and Cornelius Niemandt, “Ghanaian Pentecostal Churches’ Mission Approaches,” Journal of Pentecostal Theology 24 (October 13, 2015): 241–269.

[11] Bergunder et al., Studying Global Pentecostalism, 195.

[12] Thomas G. Bandy, See, Know & Serve the People within Your Reach (Nashville: Abingdon Press, 2013), 102.

[13] Allan Anderson, “Structures and Patterns in Pentecostal Mission,” Missionalia : Southern African Journal of Mission Studies 32, no. 2 (August 1, 2004): 243.

[14] McClung, Azusa Street & Beyond, 204.

[15] Chai, “Pentecostalism in Mission and Evangelism Today,” 119.

[16] Roscoe Lilly, “A Plan for Developing an Effective Community Outreach Strategy for Churches in the Northeast,” Doctoral Dissertations and Projects (August 1, 2013): 29.

[17] Bergunder et al., Studying Global Pentecostalism, 2.

[18] Anderson, “Structures and Patterns in Pentecostal Mission,” 233.

[19] Mark J Cartledge, Practical Theology: Charismatic and Empirical Perspectives (Eugene, Oregon: Wipf & Stock, 2012), xii.

[20] Johannes A. van der Ven and Barbara Schultz, Practical Theology: An Empirical Approach (Leuven: Peeters, 1998), 101.

[21] McClung, Azusa Street & Beyond, 204.

[22] Melvin L. Hodges, “A Pentecostal’s View of Mission Strategy,” International Review of Mission 57, no. 227 (2006): 305.

[23] Chai, “Pentecostalism in Mission and Evangelism Today,” 234.

[24] Allan Anderson, “Towards a Pentecostal Missiology for the Majority World,” Asian Journal of Pentecostal Studies 8, no. 1 (2005): 37.

[25] McClung, Azusa Street & Beyond, 162.

[26] Ibid., 147.

[27] Cartledge, Practical Theology, 12.

[28] McClung, Azusa Street & Beyond, 141.

[29] W. Saayman, “Some Reflections on the Development of the Pentecostal Mission Model in South Africa,” Missionalia : Southern African Journal of Mission Studies 21, no. 1 (April 1, 1993): 42.

[30] Murray W Dempster, Byron D Klaus, and Douglas Petersen, Called & Empowered: Global Mission in Pentecostal Perspective, 2008, 18.

[31] Anderson, “Towards a Pentecostal Missiology for the Majority World,” 39.

[32] Cartledge, Practical Theology, 11.

[33] C. A. M. Hermans and Mary Elizabeth Moore, eds., Hermeneutics and Empirical Research in Practical Theology: The Contribution of Empirical Theology by Johannes A. van Der Ven, Empirical studies in theology v. 11 (Leiden ; Boston: Brill, 2004).

[34] Cartledge, Practical Theology, 11.

[35] Bergunder et al., Studying Global Pentecostalism, 2.

[36] Gordon Alexander Carmichael, Fundamentals of Demographic Analysis: Concepts, Measures and Methods (Cham: Springer, 2016), 1.

[37] Jacob S. Siegel, David A. Swanson, and Henry S. Shryock, eds., The Methods and Materials of Demography, 2nd ed. (Amsterdam ; Boston: Elsevier/Academic Press, 2004), 1.

[38] Craig Ott and Gene Wilson, Global Church Planting: Biblical Principles and Best Practices for Multiplication(Grand Rapids, Mich: Baker Academic, 2011), 171.

[39] Richard Robert Osmer, Practical Theology: An Introduction (Grand Rapids, Mich: William B. Eerdmans Pub. Co, 2008), 54.

[40] Siegel, Swanson, and Shryock, The Methods and Materials of Demography, vii.

[41] Michele Dillon, A Handbook of the Sociology of Religion (Cambridge, U.K. ; New York: Cambridge University Press, 2003), 84.

[42] Julie C Ma, Wonsuk Ma, and Andrew F Walls, Mission in the Spirit: Towards a Pentecostal/Charismatic Missiology(San Jose: Resource Publications, 2011), 119.

[43] Ott and Wilson, Global Church Planting, 143.

[44] McClung, Azusa Street & Beyond, 213.

[45] Skip Bell, “What Is Wrong With the Homogeneous Unit Principle?: The HUP in the 21st Century Church,” Journal of the American Society for Church Growth (January 1, 2003).

[46] Aaron McAleese, Miriam Pepper, and Ruth Powell, Comparing Church and Community in 2016: A Demographic Profile, NCLS Occasional Paper 32 (Sydney: NCLS Research, 2018), 4.

[47] Miriam Pepper and Ruth Powell, Religion, Spirituality and Connections with Churches: Results from the 2018 Australian Community Survey, NCLS Occasional Paper 36 (Sydney: NCLS Research, 2018), 2.

[48] Dillon, A Handbook of the Sociology of Religion, 79.

[49] Bandy, See, Know & Serve the People within Your Reach, 12.

[50] Ott and Wilson, Global Church Planting, 156.

[51] Ibid., 157.

[52] Ibid., 156.

[53] Pepper and Powell, Religion, Spirituality and Connections with Churches.

[54] Robert E. Stevens, ed., Concise Encyclopedia of Church and Religious Organization Marketing (Binghamton, N.Y: Best Business Books : Haworth Reference Press, 2006), 43.

[55] Ibid.

[56] Bandy, See, Know & Serve the People within Your Reach, 20.

[57] Ibid.

[58] Darren Slade, Socio-Historical Examination of Religion and Ministry, 2nd ed., vol. 1 (Eugene, Oregon: Wipf & Stock Publishers, 2019), 310.

[59] Bandy, See, Know & Serve the People within Your Reach, 102.

[60] Ibid., 16.

[61] Hodges, “A Pentecostal’s View of Mission Strategy,” 305.

[62] The Globalization of Pentecostalism, 32.

[63] McAleese, Pepper, and Powell, Comparing Church and Community in 2016: A Demographic Profile, 4.

[64] Ibid., 6.

[65] Ibid., 2.

[66] Pepper and Powell, Religion, Spirituality and Connections with Churches.

[67] Ibid., 9.

[68] Ibid., 10.

[69] Gary Bouma and Anna Halafoff, “Australia’s Changing Religious Profile—Rising Nones and Pentecostals, Declining British Protestants in Superdiversity: Views from the 2016 Census,” Journal for the Academic Study of Religion 30 (October 25, 2017): 137.

[70] Michael Christopher Mason, Andrew Tintin Singleton, and Ruth Webber, The Spirit of Generation Y: Young People’s Spirituality in a Changing Australia, 1. ed. (Mulgrave: John Garratt Publ, 2007).

[71] Bouma and Halafoff, “Australia’s Changing Religious Profile—Rising Nones and Pentecostals, Declining British Protestants in Superdiversity: Views from the 2016 Census,” 137.

[72] Ibid., 131.

[73] Grace Karskens, Melita Rogowsky, and University of New South Wales School of History, “Histories of Green Square: Waterloo, Alexandria, Zetland, Beaconsfield, Rosebery” (School of History, University of New South Wales, 2004), 9.

[74] Ibid., 15.

[75] Clive Hamilton and Alex Joske, Silent Invasion: China’s Influence in Australia (Richmond, Victoria: Hardie Grant Books, 2018).

[76] Karskens, Rogowsky, and History, “Histories of Green Square,” 107.

[77] Ibid., 110.

[78] Ibid., 100.

[79] McClung, Azusa Street & Beyond, 152.

[80] Ibid., 152.

[81] Howard J. Wiarda, “New Patterns of Church Growth in Brazil. By William R. Read. Grand Rapids, Michigan: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Co., 1965. 240 Pp. $2.45 Paper,” Journal of Church and State 9, no. 3 (October 1, 1967): 410.

[82] Keith Punch, Introduction to Social Research: Quantitative & Qualitative Approaches, Third edition. (Los Angeles, California: SAGE, 2014), 3.

[83] Martyn Denscombe, The Good Research Guide for Small-Scale Social Research Projects, 2010, 269.

[84] Stevens, Concise Encyclopedia of Church and Religious Organization Marketing, 44.

[85] John W. Best and James V. Kahn, Research in Education, 10th ed. (Boston: Pearson/Allyn and Bacon, 2006).

[86] Craig A. Mertler, Introduction to Educational Research, Second edition. (Los Angeles: SAGE Publications, Inc, 2019), 111.

[87] Brian Opeskin and Nick Parr, “Population Challenges for the Local Court of New South Wales: The Next 25 Years” (2013): 45, accessed May 23, 2020, http://rgdoi.net/10.13140/2.1.3157.0560.

[88] Peter Hills et al., “Primary Personality Trait Correlates of Religious Practice and Orientation,” Personality and Individual Differences 36, no. 1 (January 2004): 61–73.

[89] McAleese, Pepper, and Powell, Comparing Church and Community in 2016: A Demographic Profile, 9.

[90] Opeskin and Parr, “Population Challenges for the Local Court of New South Wales,” 42.

[91] Ibid., 43.

[92] Population and Demographics Study, Population and Demographics Study, .id, July 19, 2018), https://s3.ap-southeast-2.amazonaws.com/dpe-files-production/s3fs-public/dpp/297774/Attachment%2021%20-%20Population%20and%20demographics%20study.pdf.

[93] Opeskin and Parr, “Population Challenges for the Local Court of New South Wales,” 43.

[94] Aude Bernard, Martin Bell, and Elin Charles-Edwards, “Internal Migration Age Patterns and the Transition to Adulthood: Australia and Great Britain Compared,” Journal of Population Research 33, no. 2 (June 2016): 124.

[95] Yu Tao and Theo Stapleton, “Religious Affiliations of the Chinese Community in Australia: Findings from 2016 Census Data,” Religions 9, no. 4 (April 2018): 1.

[96] Ian Johnson, The Souls of China: The Return of Religion after Mao, First Edition. (New York: Pantheon Books, 2017).

[97] Mason, Singleton, and Webber, The Spirit of Generation Y, 26.

[98] Janet Phillips and Joanne Simon-Davies, “Migration to Australia: A Quick Guide to the Statistics,” Department of Parliamentary Services, 2016-2017 (January 18, 2017): 7.

[99] Opeskin and Parr, “Population Challenges for the Local Court of New South Wales,” 38.

[100] McAleese, Pepper, and Powell, Comparing Church and Community in 2016: A Demographic Profile.

[101] Ibid., 12.

[102] Kathleen Kiernan, Anne Barlow, and Rosangela Merlo, “Cohabitation Law Reform and Its Impact on Marriage: Evidence from Australia and Europe,” International Family Law 63 (June 2007): 71–74.

[103] Gemma Penny, Leslie Francis, and Mandy Robbins, “Why Are Women More Religious than Men? Testing the Explanatory Power of Personality Theory among Undergraduate Students in Wales,” Mental Health 18 (July 3, 2015).

[104] Vassilis Saroglou, ed., Religion, Personality, and Social Behavior (New York: Psychology Press, Taylor & Francis Group, 2014), 330.

[105] Saroglou, Religion, Personality, and Social Behavior.

[106] Patrick M. Morley and Phil Downer, eds., Effective Men’s Ministry: The Indispensable Toolkit for Your Church(Grand Rapids, Mich: Zondervan, 2001), 17.

[107] Thom S Rainer, Surprising Insights from the Unchurched and Proven Ways to Reach Them (Grand Rapids, Mich.: Zondervan, 2001), 111.

[108] Pepper and Powell, Religion, Spirituality and Connections with Churches, 20–21.

[109] R. Powell, “Why Are Women More Religious Then Men?,” NCLS Research, last modified 2017, accessed May 25, 2020, http://ncls.org.au/news/women-more-religious.

[110] Anna Carla Liotta, Unlocking Generational Codes: Understanding What Makes the Generations Tick and What Ticks Them Off (Lake Placid, N.Y.: Aviva Pub., 2012), 55.

[111] Kaylene Williams et al., “Multi-Generational Marketing: Descriptions, Characteristics, Lifestyles, and Attitudes,” Journal of Applied Business and Economics 11 (January 1, 2010): 21–36.

[112] R. Powell, “Young Adults – 20-29 Year Olds,” NCLS Research, last modified 2003, accessed May 25, 2020, http://www.ncls.org.au/default.aspx?sitemapid=2281.

[113] Charles D. Schewe and Geoffrey Meredith, “Segmenting Global Markets by Generational Cohorts: Determining Motivations by Age,” Journal of Consumer Behaviour 4, no. 1 (September 2004): 51–63.

[114] Katherine Taken Smith, “Digital Marketing Strategies That Millennials Find Appealing, Motivating, or Just Annoying,” Journal of Strategic Marketing 19, no. 6 (October 2011): 489–499.

[115] Aaron Smith and Monica Anderson, “Social Media Use in 2018” (Pew Research Center, March 1, 2018).

[116] Ibid., 2.

[117] Mairead Shanahan, “Marketing and Branding Practices in Australian Pentecostal Suburban Megachurches for Supporting International Growth” (Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill, 2020), 133.

[118] Henrietta M. Nyamnjoh, “‘When Are You Going to Change Those Stones to Phones?’ Social Media Appropriation by Pentecostal Churches in Cape Town,” Journal for the Study of the Religions of Africa and its Diaspora, no. 5 (2019): 139.

[119] Rosalind I. J. Hackett and Benjamin F. Soares, eds., New Media and Religious Transformations (Bloomington ; Indianapolis: Indiana University Press, 2015).

[120] Nyamnjoh, “‘When Are You Going to Change Those Stones to Phones?’ Social Media Appropriation by Pentecostal Churches in Cape Town,” 139.

[121] Conrad Hackett et al., The Age Gap in Religion Around the World, 2018, 1.

[122] Xuefeng Zhang, “How Religious Organizations Influence Chinese Conversion to Evangelical Protestantism,” Sociology of Religion 67, no. 2 (June 1, 2006): 149–159.

[123] Ibid., 152.

[124] Denise A Austin, “Mary (Wong Yen) Yeung: The Ordinary Life of an Extraordinary Australian Chinese Pentecostal,” American Journal of Political Science 16, no. 2 (2013): 99–122.

[125] Nanlai Cao, “The Church as a Surrogate Family for Working Class Immigrant Chinese: An Ethnography of Segmented Assimilation,” Sociology of Religion 66, no. 2 (2005): 196.

[126] Dennis Franck, Reaching Single Adults: An Essential Guide for Ministry (Grand Rapids, Mich: Baker Books, 2007), 59.

[127] Ibid., 83.

[128] Franck, Reaching Single Adults.